Latest News

- Kuwait-Jordan Durra Field Joint Statement Rejected By Iran

- GTD Cracks Down On Vehicle Noise Pollution In Sulaibiya

- Mystery Of Dead Fish At Shuwaikh Beach Sparks Urgent Action

- MEW To Complete Links With The Interior And Justice Ministries B...

- 8 Expats Jailed For Bribing An Officer To Obtain Driver's Licens...

- Weekend Weather Is Expected To Be Hot

- From Tomorrow, Traffic Diversion On Third Ring Road

- Ministry Of Health Refute Rumors On Non-availability Of Antibiot...

- Amir Of Kuwait And Jordan King Renew Commitment To Regional Secu...

- 37 Arrested With Narcotics And Firearms

- Outrage Over Candidate's Arrest

- Six Stores Shut Down In Jahra For Selling Fake Goods

Mp Hashem Blames Foreigners As Gcc Austerity Sets In

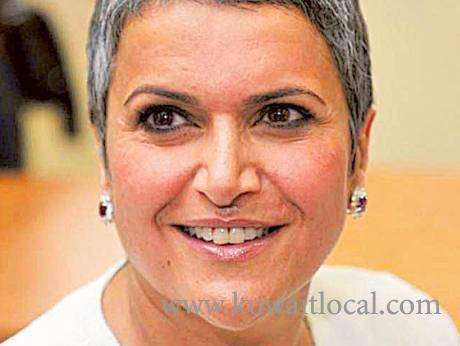

Safa Al Hashem, the only woman in Kuwait’s 50-seat parliament, is capitalising on a growing resentment of foreigners to build support for a movement that’s taking shape as the nation’s ruling Al Sabah family withdraws some handouts in an era of cheap oil. “Before asking citizens to pay, the government should reform the population mix by levying taxes on foreigners," said the 52-year-old former investment banker, whose salt-and-pepper pixie-cropped hair and attire of smart business suits make her stand out among exclusively male counterparts in national dress. “The citizen feels that our entitlements lack social justice.”

Voices of discontent in Kuwait’s legislature, the most-independent in the Gulf, provide a rare glimpse into how locals are reacting as cash-strapped governments from Saudi Arabia to the UAE overhaul social contracts.

Kuwait’s rulers “have to manage a very delicate transition,” said Graham Griffiths, an analyst at global risk consultancy Control Risks in Dubai. “The issue for them is managing the economic reforms they see as necessary, while placating populist pressures amid broader demand for political reform and accountability.”

Al Hashem’s brand of populism is unique to the nation of 4.4 million, where migrant workers outnumber locals 3-to-1 and, unlike elsewhere in the Gulf, get subsidized health care and education. It’s all the more striking because the nation survives because more than two dozen countries came to its rescue 26 years ago to force out Saddam Hussein.

She wants the Egyptians, Syrians, Indians and Bangladeshis who do the plumbing and teach students to be deported, or get taxed for “walking on the roads” if they stay. “They’re sucking up the state’s resources,” said the Harvard Business School graduate, who won her seat in a November election that saw Kuwaitis oust more than half of the incumbents to protest the first gasoline price hike in decades, which took the cost of premium fuel to 165 fils (55 cents), up 83 percent according to local press.

The message is gaining traction. Al Hashem, who has more than 400,000 followers on Twitter, has been elected three times since late 2012. Meanwhile, pressure is intensifying for Kuwait to cut a subsidy bill that mushroomed five-fold to KD 5.1 billion dinars ($17 billion) in the decade to 2015. Reluctant to deplete its $592 billion wealth fund meant to preserve cash for future generations, the nation borrowed from the international debt markets for the first time last month, raising $8 billion.

Regular clashes between lawmakers and government officials appointed by the Al Sabahs have delayed investment projects in recent years, leaving Kuwait behind peers in weaning its economy off oil. While parliament can make laws, veto state decisions and hold ministers to account, Amir Sabah Al Ahmed Al Sabah regularly dissolves it when tensions run too high.

It last happened in October after ministers came under fire for the subsidy cuts. But the election weeks later bolstered an opposition united in blaming foreigners for deteriorating public services.

Among them is Abdulkarim Al Kandari, who holds a doctorate in commercial law from University of Strasbourg in France.

One evening last month in Kuwait City, he convened with nearly two dozen citizens for a traditional diwaniya, a gathering where Kuwaiti men sit on wall-to-wall sofas to discuss the issues of the day. The banner hanging above them in Arabic read “the population imbalance,” a telling indication of a pressing worry.

“We are not setting up a Trump wing here,” Al Kandari said, refuting the idea that developments in Kuwait resemble the anti-immigrant sentiment that catapulted Donald Trump to the White House and boosted Marine Le Pen’s popularity in France. “But dealing with a deficit means we must rethink our policies.”

Speaking as two Egyptian kitchen staff served tea and Arabic coffee, Al Kandari said his beef isn’t with the guest workers who build skyscrapers, drive cabs or work in services. Kuwaitis don’t want those jobs anyway. But he doesn’t think foreigners should fill professional jobs, such as administrators and teachers when official unemployment among locals is 4.7 percent.

Part of the issue is pay since migrant workers accept a fraction in wages. University-educated Kuwaitis earned a median of KD 1,350 ($4,426) a month in 2015 versus 490 for similarly qualified expatriates, according to official statistics.The overall wage discrepancy was even starker: KD 1,113 versus KD 120 .

A recent survey of several Kuwaiti nationals showed opinion is divided on the urgency of change. Khalid Bouaraki, a government employee, said compatriots upset over subsidy cuts are “overreacting” because they can afford it. Perks exclusive to citizens include free land plots to build homes, interest-free loans, university and marriage grants and the occasional state write-off of consumer debt.

On the other hand, Yousef Mohamad, a 49-year old state employee, is suffering because his salary hasn’t gone up in years. “Not all of us are rich,’’ the father of four said, while sipping tea in a local cafe. “Many of us are struggling to land secure jobs."

Along with lowering its dependence on oil and modernizing infrastructure, Kuwait’s 2035 development plan envisions reducing the proportion of foreigners to 60 percent from the current 70 percent, according to local media.

But appeasing such people as Al Hashem, who wants businesses to take the burden from the state for funding benefits for foreigners, will take more than that. Since securing her seat, she’s won support for a bill to overturn the petrol price increase, lobbied vigorously to make migrant workers buy medical insurance and proposed an expat-only road tax to ease traffic congestion.

“I won’t remain silent just to keep our boat sailing,” Al Hashem said. “Citizens would be willing to pay their fair share, but not when they know their money will go to pay for the others.”

Trending News

-

Kuwait Implements Home Biometrics Services Ahead O...

14 April 2024

Kuwait Implements Home Biometrics Services Ahead O...

14 April 2024 -

Kuwait Airways Provides Update On Flight Schedule...

14 April 2024

Kuwait Airways Provides Update On Flight Schedule...

14 April 2024 -

Kuwait Airways Introduces Convenient Home Luggage...

15 April 2024

Kuwait Airways Introduces Convenient Home Luggage...

15 April 2024 -

Expat Residency Law Amended By Kuwait Ministerial...

20 April 2024

Expat Residency Law Amended By Kuwait Ministerial...

20 April 2024 -

Two Expats Are Arrested For Stealing From Salmiya...

17 April 2024

Two Expats Are Arrested For Stealing From Salmiya...

17 April 2024 -

An Egyptian Expat Dies At Kuwait's Airport

11 April 2024

An Egyptian Expat Dies At Kuwait's Airport

11 April 2024 -

Bay Zero Water Park Kuwait: Summer Season Opens Ei...

11 April 2024

Bay Zero Water Park Kuwait: Summer Season Opens Ei...

11 April 2024 -

Kuwait Airways Resumes Flights To Beirut And Oman...

15 April 2024

Kuwait Airways Resumes Flights To Beirut And Oman...

15 April 2024 -

Temperature Increases Cause Electricity Load Index...

21 April 2024

Temperature Increases Cause Electricity Load Index...

21 April 2024 -

Thief Returns Stolen Money With An Apology Letter...

15 April 2024

Thief Returns Stolen Money With An Apology Letter...

15 April 2024

Comments Post Comment